by Jenny Saunt

- Chair #37

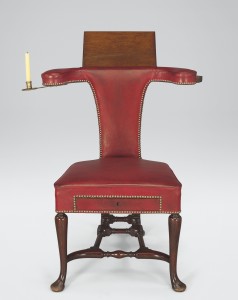

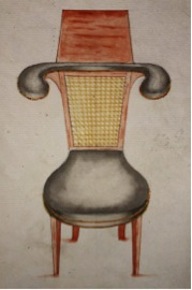

This mid eighteenth-century chair is loaded with features and gadgets, the purposes of which have caused much discussion and speculation in twentieth-century furniture histories.

Aside from its intriguing form, of narrow back and broad shoulders, the chair also has a multi-adjustable board on the back, a swing-out candle stick and pocket in either side of its shoulders and a drawer in the front of its seat.

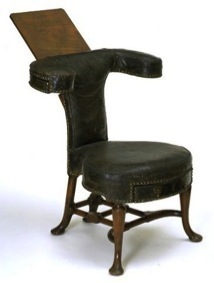

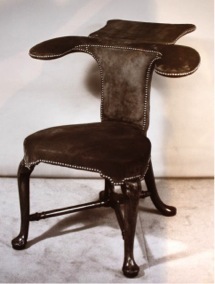

Other chairs of this type follow the same basic format. A V&A example (below left) shares exactly the same structure of stretcher and similar appliances, while another variation (below right, from the Robin Kern Hotspur image collection) offers a different solution for the stretcher and only an adjustable back-board.

Other chairs of this type follow the same basic format. A V&A example (below left) shares exactly the same structure of stretcher and similar appliances, while another variation (below right, from the Robin Kern Hotspur image collection) offers a different solution for the stretcher and only an adjustable back-board.

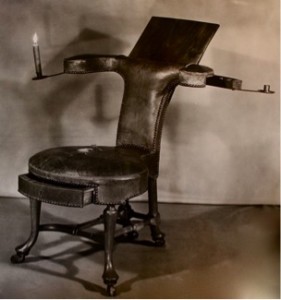

A slightly later variety (below) does-away with the stretcher and seat-drawer altogether, but compensates with extra heavy-weight storage space in deeper shoulders.

Curiosity over this chair form resulted in it collecting several aliases throughout the twentieth century: a reading chair; a writing chair; and most popularly, a cock-fighting chair.

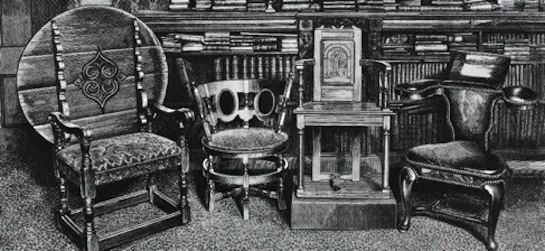

These chairs were objects of curiosity in the nineteenth-century too – one made an appearance in an 1878 illustration of the collection of George Godwin, editor of ‘The Builder’. Godwin titled the assortment below ‘Suggestive Furniture’ and displayed this collection of chairs in his London house.

In the twentieth century, ‘Cockfighting Chair’ became antique dealers name of choice for chairs of this type.

The eighteenth-century cockfight was brought vividly to life by William Hogarth, who showed spectators resting elbows on the ringside and straining forward in an atmosphere full of intent, chaos, focus and anxiety.

Hogarth even provided a portrait of a bookkeeper, whose position makes it easy to imagine how much more comfortably and stylishly accommodated he would have been in a purpose made chair – perhaps something designed specifically to support his elbows, with a rest for his open book?

Another often proposed identity for this chair type is the ‘Writing Chair’. However, eighteenth-century depictions are clear upon this matter, as can be seen below, writing required a large open surface so that the entire arm was free to move.

The fixed pad-rests of the CTF chair would have proved too restrictive for the eighteenth-century gentleman’s writing posture.

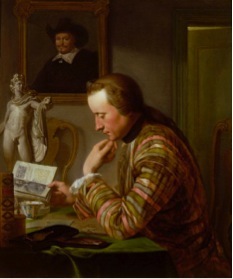

Finally, there is the possibiltiy that this was a ‘Reading chair’. Depicted reading postures of the eighteenth-century show the activity to be an upright and gentlemanly pastime of great concentration – for which a good light source was estential. Both the gentlemen shown below would have been well served by a ‘Reading Chair’.

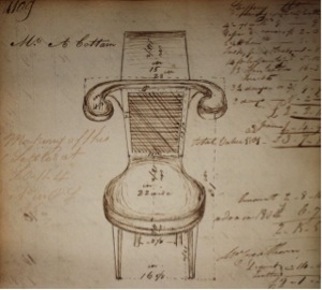

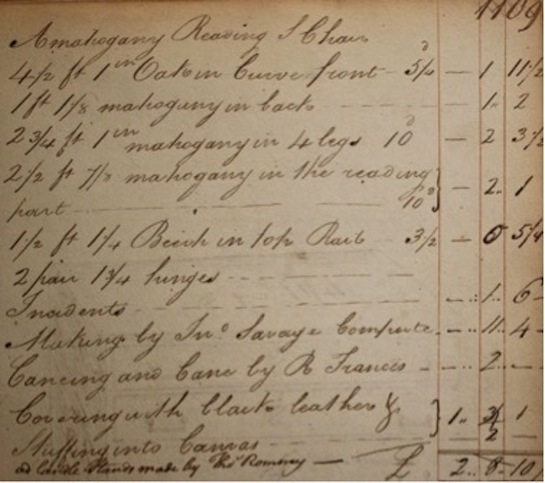

Evidence of the eighteenth-century demonstrates that reading was the purpose for which this chair was designed. Although the cockfighting identity is appealing (and has no doubt added something to the value of these chairs over the years), sources contemporary to this chair type state clearly that it was designed as a reading chair – as can be shown in the Gillow sketch estimate books of 1794.

The costings for the drawings pictured above are clearly headed ‘A Mahogany Reading Chair’.

This title fits with a writen description of a reading chair that the designer Thomas Sheraton (1751-1806) provides in The Cabinet Directory in 1803,

“intended to make the exercise of reading easy, and for the convenience of taking down a note or quotation on any subject. The reader places himself with his back to the front of the chair and rests his arms on the top yoke”.

Not as exciting as being part of a fantasy eighteenth-century cockfight, but a clear description of this chair nonetheless.

References:

V&A Reading chair W.131:1, 2-1970

Hotspur Antiques, Chair files.

- Godwin’s ‘suggestive furniture’: Susan Webster-Soros, The Secualar Furniture of E.W. Godwin, (Yale University Press (1999), p. 68.

Gillow Archive, Westminster Archive, Gillow sketch pattern books and estimate books.

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Directory, 1803.