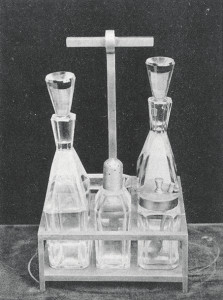

Writing in Architectural Review in 1937, the German-born architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983), by then living in London, noted, “While engaged in research on the origins of the Modern Movement quite by chance I came across the name and two isolated examples of the work of Christopher Dresser.” The works to which Pevsner referred, and which he illustrated in the article, are electroplated nickel silver and glass cruets manufactured by Hukin & Heath of Birmingham around 1878 (figs. 1–2). These practical objects represent a stark contrast to the fussy production that was a feature of so much mid-nineteenth-century British manufacture. Such pieces are invariably seen today as anticipating the functional, pared-down aesthetic that typifies the work of designers who followed: Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928), Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956), Christian Dell (1893–1974), Marianne Brandt (1893–1983), and others. But as much as Dresser is admired for his protomodern aesthetic, he was also a typically curious Victorian with an informed knowledge of historic sources and an understanding of color and texture. This catalogue illustrates some of the apparently contrasting, but in fact complementary, elements of his work.

- Figure #1

- Figure #2

The manufacturer Hukin & Heath registered the design for a claret jug (no. 28) on October 9, 1878. This model, today commonly known as the “crow’s foot decanter,” combines several recurring features from Dresser’s work, including humor. The claret jug’s avian form, with its beaklike spout and pointed feet, is a much less decorated variant of the ubiquitous decanters more obviously representing birds that graced the middle-class dining rooms of Victorian Britain (often made of ruby glass with silver-gilt mounts). In Dresser’s example, the protruding, pointed tail of a bird (here the glass body) is transformed into an abstract, symmetrical vertical: the designer has stripped away the decoration and created a form that is both practical and elegant. As with many of Dresser’s designs, it pays to imagine this as a simple silhouette.

Since Pevsner’s publication of Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936), which included a discussion of Dresser’s work, and his Architectural Review article (1937), the designer has been held in increasingly high esteem. There were twenty works by Dresser in the important Exhibition of Victorian & Edwardian Decorative Arts mounted at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in 1952. On that occasion, the “Claret Jug (Height 10 in.) glass, mounted with silver lid handle and feet,” as referenced in the exhibition’s catalogue, may have been a “crow’s foot decanter”. Dresser has now also been the subject of numerous monographic exhibitions, beginning with Christopher Dresser, mounted by Richard Dennis, John Jesse, and the Fine Art Society in 1972. This was followed by the designer’s first noncommercial exhibition, Christopher Dresser, 1834–1904, held at the Camden Arts Centre in 1979. In 2001 ‘Christopher Dresser: A Designer at the Court of Queen Victoria’ was mounted in Milan, and the following year Christopher Dresser and Japan toured four Japanese museums, taking the designer’s work to a country that he had visited and that had been a considerable source of inspiration for him.

More recently the Cooper Hewitt, New York, and Victoria and Albert Museum mounted Shock of the Old: Christopher Dresser’s Design Revolution (2004), an authoritative appraisal of the designer’s work. Dresser’s production in many media—ceramics, furniture, glass, metalwork (silver, electroplated nickel silver, painted tin, and cast iron), textiles, and wallpaper—is now represented in museum and private collections across the globe. There is no longer any question of his internationally accepted reputation as the leading “Viktoiranischer Designer,” as a 1980 monographic exhibition mounted at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Cologne, called him.

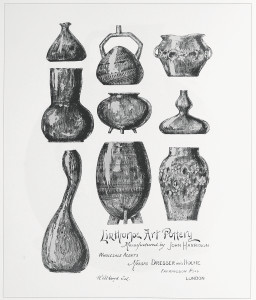

In later life, Dresser’s significance and originality were admired in the pages of The Studio (founded 1893), published by his friend and sometime collaborator Charles Holme. Although manufacturers such as the Linthorpe Art Pottery, James Couper, and James Dixon appear to have used Dresser’s talent as a selling point, adding his name to their makers’ marks, “The Work of Christopher Dresser,” published anonymously by The Studio in 1898, is the only tribute to the designer to appear before his death.

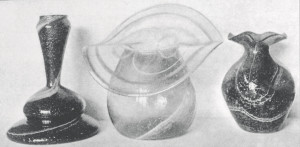

The Studio’s 1898 article includes twelve examples of “Clutha” glass by J. Couper & Sons, including the image of three vessels shown here (fig. 3), the center one of which is a vase of the same pattern as no. 20 in this catalogue. This remarkable, flowerlike creation is perhaps a reminder of Dresser’s training as a botanist. The metal inclusions in the body of the vase glisten like dew in the early morning light. The vase, like much of the Clutha range, retailed through the London department store Liberty & Co. (founded 1875) and was available in four sizes, ranging in height from four to eight inches. Couper was based in Glasgow, and Clutha is the Latin name for the Clyde, the river that runs through that city.

- Figure #3

Dresser often drew directly from exotic or historic sources for his glass and ceramics: the Clutha bottle-shaped vase (no. 14), for example, was derived from seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Persian rose-water sprinklers. In his Principles of Decorative Design (1873), Dresser wrote, “In order that you acquire the power of perceiving art-merit as quickly as possible, you must study those works in which bad taste are really met with, you must at first consider art-objects from India, Persia, China, and Japan, as well as ancient art from Egypt and Greece.” Judy Rudoe, writing in Christopher Dresser: A Design Revolution (2004), noted that this statement “reveals in a nutshell [Dresser’s] debt to the art of ancient and contemporary civilizations alike.” In Studies in Design (1876), Dresser echoed Owen Jones in urging students “to study whatever has gone before; not with the view of becoming a copyist, but with the object of gaining knowledge, and seeking out the general truths and broad principles . . . [so that] our works should be superior to those of our ancestors, inasmuch as we can look back upon a longer experience than they could.”

The Studio article, “The Work of Christopher Dresser” also picks up on several of the designer’s themes that are recognized today. This article noted its appreciation for Dresser as “perhaps the greatest of commercial designers imposing his fantasy and invention upon the ordinary output of British industry.” In the world of design, it went on, “Dresser is in a way the figure-head of the professional . . . a household word to people interested in design,” with a talent for raising “the national level of design . . . by dealing with products within the reach of the middle classes, if not the masses themselves.” The anonymous writer also admired the practical nature of Dresser’s “designs for jugs, teapots, and other vessels for fluid, in which the position of the handle is determined by the laws of gravity, so the vessel when full could be held with the least possible strain on the muscles of the holder” (see, for example, no. 34).

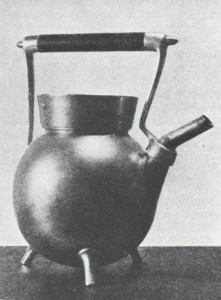

- Figure #4

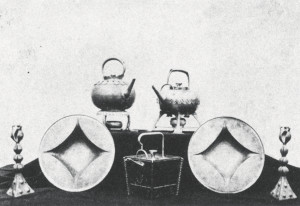

That Dresser designed for Benham & Froud is confirmed by the five varied examples of the firm’s work shown in The Studio article, as well as by Pevsner’s illustration of Dresser’s spherical tripod kettle (fig. 4), an example of which is also included in this catalogue (no. 36). The spherical or cauldron form, raised on three short legs, is a recurring theme in Dresser’s metalwork (see, for example, nos. 26, 29, and 34). The tripod supports, which can be seen on medieval iron cauldrons, offer stability and create lightness for the solid bodies they hold. Another distinctive feature of the copper and brass vessels designed by Dresser for Benham & Froud is the visible rivets that attach the various elements. These are evident in the designer’s Japanese-inspired kettle (no. 40) and kettle on a stand (no. 41), which can be compared to those illustrated in a photograph of Benham & Froud pieces c.1882. (fig. 5), from the Chubb archives.

- Figure #5

Dresser’s work in different media sometimes uses the same or very similar shapes. Compare, for example, an Ault earthenware vase (no. 12) with one of his Clutha vases (no. 17). Although the solid ceramic body and the translucent glass create contrasting effects, the objects are actually quite similar when considered as silhouettes. Dresser also employed ornament and glazes to create different impressions among objects with the same form. One of the Ault vases featured in this catalogue (no. 13) is part of a group of yellow-glazed vases in which form is emphasized by the strong monochrome glaze. But a different effect emerges when the same model uses other colors, more variegated glazes, or even decorated surfaces. Examples of the same Ault vase form are recorded with solid green and solid red glazes; with a streaky blue, black, and white glaze; with incised decoration; and even with a turquoise interior and pink exterior, painted with geometric decoration.

- Figure #6

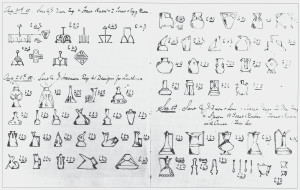

Early in his career, Dresser produced some extraordinary graphic designs for vases by Wedgwood and then Minton. But the later ceramics that he designed for Linthorpe, for example those advertised in the Furniture Gazette, 1880, here fig. 6, are intriguing in different ways. Taken as a group, these pots bring together two strands of Dresser’s design: the quirky forms that were derived from both ancient prototypes and his own original creations. These sharply angled, often monochrome forms can be seen as the ceramic incarnation of his much-vaunted angular metalwork. One jug (no. 3) is directly based on a Cycladic jug of a type dating from 2200–1800 B.C., and a masked vessel (no. 9) is based on Pre-Columbian Nasca vases; other ceramics inspired by distant sources are legion, including vases based on Japanese, Egyptian, Peruvian, and English Prehistoric and Bronze Age vessels. A plain, hemispherical jug with an angular handle (no. 17) may represent the type of more idiosyncratic designs for ceramics that emanated from Dresser’s fertile imagination. In the drawings from his 1881 account books, illustrated by Pevsner (fig. 7), both these protomodernist and cross-cultural elements are clear.

- Figure #7

Despite the evident diversity displayed in the ceramics, glass, and metalware included in this catalogue, there is an equally apparent unifying element: Dresser’s eye for form. Although in his textiles and other two-dimensional works, Dresser was a prolific and original creator of ornament, in the present collection, decoration plays a secondary role to shape. The protomodern aesthetic of Dresser’s tableware and the adventurous treatments of his cross-cultural ceramics reveal the particular elements of Dresser’s eye and mind that appeal so much to our contemporary tastes. But his use of color, too, perhaps anticipates some of the playfulness of postmodernism.