by Jenny Saunt

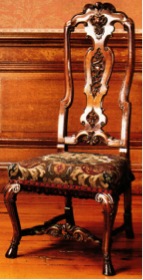

Though previously bought and sold several times as seventeenth-century pieces, this pair of CTF chairs (only one shown here) have recently revealed their true identity as creations of the nineteenth-century.

Several significant pieces of evidence have led to this re-dating.

First, the construction technique – with screwed-in corner brackets – suggests the work of a nineteenth-century furniture maker. The un-patinated surface revealed when the brackets are removed proves they were always part of the chair’s frame and so dates the chairs to the nineteenth-century without doubt.

Second, the wood used for the original corner blocks has been identified by Adam Bowett as either birch or maple – not woods used by seventeenth or eighteenth-century English chair makers.

Third, the screws from the original corner bocks are handmade and of mid nineteenth-century origin – confirmed by the cut across the top, which is uneven in depth and off-centre.

Finally, in an attempt to put an absolutely certain date on these chairs they have recently been carbon dated. Unfortunately the results of the carbon dating were not conclusive, but one of the more likely periods in which this timber was originally cut does tally with the chair being constructed in the nineteenth century.

Chairs of this type have frequently been referred to as ‘Marot chairs’ – a reference to the seventeenth and eighteenth-century designs of Daniel Marot and the style of decoration on the chair’s carved splat (compared to Marot’s prints below).

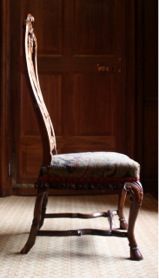

The name ‘Marot’ is also connected to the date of production for some of these chairs. For example, at Hampton Court there is a large set of seventeenth-century chairs almost identical in design to the nineteenth-century CTF chairs. Two of the Hampton Court chairs are pictured below.

With a passing glance, the CTF chair (below left) is very similar to the Hampton Court set (below right).

However, a close comparison reveals the differences more clearly.

On the Hampton Court chair-backs there is a more nipped-in waist, the curve of the splat is fuller, all of the curves in the chair are very slightly rounder and fuller, and the style of the carving is looser. Besides these differences, the patina of the Hampton Court chair is clearly that of an older chair, with pitting, staining, dents and chips. There are even places where whole sections of decoration have been broken off this set through more than 300 years of use.

The nature of the carving on the Hampton Court chair provides more interesting comparisons, it is heavily marked with the traces of the tools that made it and in a strong sidelight these reveal themselves clearly.

Furthermore, the blocking-out pieces which have been added to the front face of the chair, at points of high-relief decoration, are in line with late seventeenth/eighteenth-century modes of construction.

In the image below, a faint line can be seen running horizontally across – between the most projecting parts of the decoration and the main frame. This indicates where additional blocks have been glued onto the frame to enable the carver to make ornament with greater projection.

When compared directly with the seventeenth-century Hampton Court chairs, the clean finish of the CTF ‘Marot’ chairs looks too pristine. Nevertheless, the CTF chairs are still an excellent example of the best nineteenth-century furniture making and are also part of the historicist turn outlined by Adam Bowett’s introduction to this subject.

Despite it now seeming obvious that this pair of CTF chairs are nineteenth-century pieces, such chairs have for a long time been published in furniture history books and discussed as examples of late seventeenth/early eighteenth-century furniture making.

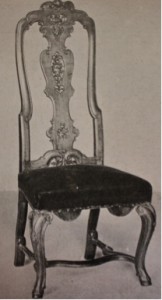

There are several design variations in the nineteenth century versions. For instance, the CTF Marot chairs have an indentation in the underside centre of the front seat rail, which suggests they were once decorated with a scalloped front edge – like the two chairs shown below.

Though these two chairs look similar, the outline of the splat reveals they are different chairs – the square-ended section halfway down the side of the splat is different in each.

For other design alternatives, an internet search for ‘Marot chair’ throws up many variations on the theme (see below), but without examination it’s impossible to say which of the chairs below are actually the seventeenth-century pieces they all claim to be.

The 1880 photograph below shows a ‘Marot chair’ prominently displayed in a showcase fashionable interior and it is possible that the date of this image provides a clue to a period of prolific production for this chair type.

However, this is a chair design of long standing appeal because, in addition to the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century examples of the chair already considered, it was also in production in the twentieth century.

The photograph of the Saddlers Hall, below, showcases a set of these chairs which were made as a gift for the guild in 1951.

So, while all chairs of this form should clearly be considered carefully for clues of dating, the one certainty of ‘Marot’ chairs is the enduring appeal of their design: a design which has motivated makers to revisit it repeatedly over the course of more than 300 years.

References:

W. Symonds, English Furniture From Charles II to George II, fig. 21, p. 42

W. Symonds, Old English Walnut and Lacquer Furniture, pl. `vi, p. 44

Maquoid & Edwards, The Dictionary of English Furniture, Vol. i., ill. fig.82,83, p.253

Edwards, M. Jourdain, Georgian Cabinet Makers, rev edn., 1962 p.126, pl. 10

Lenygon, Furniture in England from 1660 to1760, rev edn., 1924, p.41

Adam Bowett, ,Early Georgian Furniture 1715-1740, (Antique Collectors Club, 1988), p. 164

Herbert Cesinsky, English Furniture of the Eighteenth century, Vol. 1, p. 52

Lucy Wood, The Upholstered Furniture in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, 2 Vols, (Yale university Press/National Museums Liverpool, 2008), p. 1022, 1033 (similar chairs)