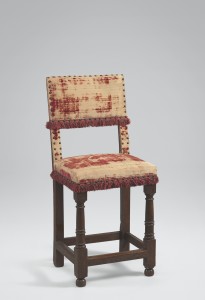

The chairs in this section span about a century and illustrate a period of remarkable stylistic and material change. Some types of chairs, such as the upholstered backstool and its armed counterpart (8, 9), changed little during the course of the seventeenth century.

- Chair #8

- Chair #9

The simple, boxy form was economical to make and to upholster. Turkey-work and leather upholstery were particularly popular because of their modest cost and durability, and were commonly found in ‘middling’ and upper-class homes. Much leather was imported, especially from Russia, and Turkey-work was so called because of its resemblance to Oriental carpets. It was made in several parts of England, but particularly in Yorkshire, from whence it was carried to London for sale. Its popularity was accounted for by its modest price, bright colours, and durability.

Wooden backstools or chairs showed greater variation, revealing different styles existing in parallel. The Lancashire and Manchester backstools (10, 11) and the twist-turned chair (14) are probably contemporary in date, but in stylistic terms the first two look back to the 1630s, while the third embodies the new fashions of the 1660s.

- Chair #10

- Chair #11

- Chair #14

Even more radical were the cane chairs (12,13,16,17), which replaced traditional upholstery or panelled backs and seats with woven strips of cane imported from the Far East.

- Chair #12

- Chair #13

- Chair #16

- Chair #17

These chairs first emerged in London in the 1660s and by 1700 were probably the most common seating type found in middle- and upper-class English houses. Their rapid stylistic development means that they can be closely dated, as innovation followed innovation over a period of about fifty years, until, about 1710–15, they began to fall from favour.

Cane chairs aside, most new furnishing ideas came from France. The scrolled-leg or horsebone chair (7) was an English variant of the fashionable French os de mouton chair developed in Paris in the 1670s.

- Chair #7

- Chair #7 detail

By 1700 it had reached its ultimate development and was probably the most common design of upholstered chair found in high-status houses.

The pillar-leg or cross-frame chair (20), so called because of the shape of its legs and stretchers, respectively, was another French innovation that became popular in England in the 1690s and remained in fashion until the 1720s. Upholstery fabrics were available to suit most pockets, ranging from plain English woollens to colourful needlework, silk damask, and rich velvet.

- Chair #20

These stylistic changes occurred against a background of rapid economic growth created by burgeoning overseas trade, which created both a demand for luxury and the means to pay for it. The manufacture of upholstered furniture in silk, velvet, and wool, in greater quantities than ever before, is one manifestation of the new wealth. It is fair to say, however, that the survival rate of these more expensive fabrics has been greater than that of plain English woollens, so we have a somewhat skewed impression of everyday furnishings of this period.

Outside London the pace of change was much slower. Local materials and traditional forms persisted in rural and remote areas, often with only the slightest acknowledgement of metropolitan fashions (18, 19). This was often a question of choice rather than necessity, testifying to the importance of local values in rural societies.

- Chair #18

- Chair #19