The increasing prosperity of eighteenth-century Britain was reflected in the houses and furnishings of its people. What were once rarities became commonplace, and former luxuries became widely available. Woollen cloth, Britain’s staple manufacture and once the universal choice for clothing, bedding, curtains and upholstery, increasingly gave way to imported cottons, silk and velvets. However, unlike chair frames, which are robust and can be repeatedly repaired, cloth is fragile and rarely survives intact. Consequently, only one of the chairs in this section (43), and possibly one other, retains its original upholstery. The broad back and seat give maximum exposure to the colourful tapestry, which is set off with carved and gilded woodwork.

- Chair #43

Most of the other chairs do, nevertheless, have genuine eighteenth-century needlework covers, and this is a testament to the popularity of this type of fabric. It was colourful, was relatively hardwearing, and could easily be repaired; every Georgian girl was taught needlework from an early age, and this might well account for its high survival rate. Even when past repair for daily use, it was often preserved for its decorative value.

- Chair #38

- Chair #39

- Chair #42

All the chairs in this section have particular roles – none are dining chairs. Three are back-chairs (38, 39, 42), eighteenth-century versions of the backstool, and originally belonged to larger sets that might well have included armchairs and sofas. Such chairs were found in drawing rooms, best parlours and bedchambers. Two are easy chairs (40, 41), which we now commonly call wing chairs. This type of chair was developed at the end of the seventeenth century and was originally used in bedchambers and dressing rooms. Some were made to be adjustable so that the occupant might doze or sleep without actually going to bed (41). By the end of the eighteenth century such chairs had begun to migrate into parlours and drawing rooms as well.

- Chair #40

- Chair #41

Two are plain armchairs (33, 34) and could have been used in almost any room in the house; there could well have been matching back-chairs as well.

- Chair #33

- Chair #34

Two others are dressing chairs, with low backs to allow the sitter’s hair to be powdered and dressed (35, 36). In the nineteenth century such chairs became redundant, their purpose forgotten, and they became known to connoisseurs and collectors as writing chairs.

- Chair #35

- Chair #36

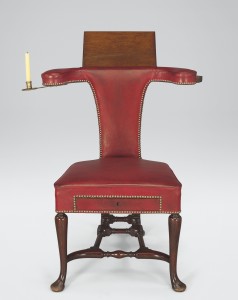

One chair (37) is a purpose-made writing chair with a folding desk at the back and candle slides and a pen drawer housed in the arms. The writer would sit reversed with his arms on the back, the desk in front of him, and candle and pen to each side.

- Chair #37

- Chair #43

The frames of these chairs were designed primarily as vehicles to display upholstery, so decoration is largely confined to carved details on the legs and arms. Claw feet, shell knees and masks reveal neo-Palladian influence, while the scrolling, leafy decoration of one of the chairs in this section (43) heralds the arrival of the rococo.