The Gothic Revival was the most powerful British artistic, architectural, and cultural movement of the Victorian age. In the early part of the period its chief protagonist was Augustus Welby Northmore (A.W.N.) Pugin (1812–1852). For Pugin the Gothic or Christian style embodied an era that was artistically and morally superior to the ‘pagan’ classicism that had prevailed in Europe since the Renaissance. In Contrasts, his seminal work on Gothic architecture published in 1836, Pugin argued for ‘a return to the faith and social structures of the Middle Ages’. But he was no slavish imitator of medievalism, and many of his furniture designs have a directness and simplicity that, while Gothic in spirit, is virtually timeless (55).

- Chair #55

It was Pugin who developed the concept of ‘revealed construction’, by which the structure of an object was directly expressed in its design. Revealed construction became one of the key dogmas of the later nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement.

In his book True Principles (1841) Pugin stated: ‘The two great rules for design are these: 1st, that there should be no features about a building which are not necessary for convenience, construction, or propriety; 2nd, that all ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building’.

Pugin’s son, Edward Welby (E.W.) Pugin (1834–1875), took over his father’s practice and continued his work in a similar style. He adhered to his father’s philosophy of revealed construction and yet managed to create new forms that were both Gothic and modern simultaneously (58).

- Chair #58

A.W.N. Pugin had many admirers, and the second generation of Gothic revivalists included several highly original talents. George Edmund (G.E.) Street (1824–1881) spent all his life working in the Gothic style, initially as an ‘improver’ of existing buildings and later as a creator of new ones. The building of the new Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand, London, is his best-known and most prestigious commission (59).

- Chair #59

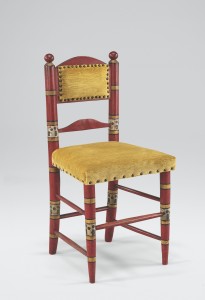

Another talented architect-designer was the idiosyncratic William Burges (1827–1881), who inherited sufficient wealth to spend the first half of his life travelling and studying medieval art. His career as a professional architect began in the offices of Edward Blore (1787–1879) in 1844, but by 1856 he had established his own practice. His version of Gothic combined medieval French with Moorish and other influences, expressed in robust forms and strong colour (60).

- Chair #60

E.W. Godwin (1833–1886), a friend of Burges, began his career as an architect in the Italianate Gothic style, but he was also powerfully impressed by the art of Japan, which was just beginning to be known in Europe in the 1860s. His early work, such as the Northampton Guildhall (56), was robustly conceived in the Gothic manner, but he quickly moved on to a lighter, Japanese-influenced style in the 1870s and 1880s.

- Chair #56

- Chair #57

In the 1860s the Gothic style was rapidly adopted by provincial furniture-makers in all parts of Britain (57). The Gothic Revival furniture, both in its muscular form as well as in a lighter vein, was manufactured by firms throughout the north of England all during the third quarter of the nineteenth century. These firms often made use of the same designers

and drew from the same design sources.